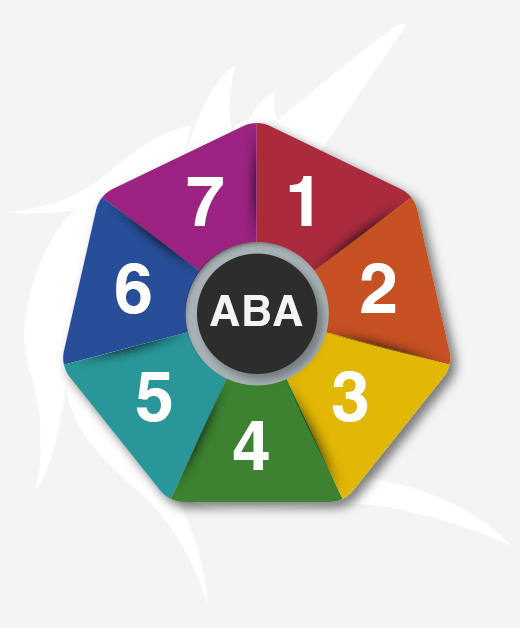

The seven dimensions of ABA

The term Applied Behavior Analysis appeared for the first time in 1968, in the JABA (Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis).

In the same year, Baer, Wolf and Risley published an article, “Some current dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis”, which is considered to be at the basis of ABA, in which they identified the 7 fundamental dimensions of the subject matter. Let’s see what they are:

First dimension: Applied

According to the authors, “the behavior, stimuli, and/or organism under study are chosen because of their importance to man and society, rather than their importance to theory. A primary question in the evaluation of applied research is: how immediately important is this behavior or these stimuli to this subject”.

“The non-applied researcher may study eating behavior, for example, because it relates directly to metabolism, and there are hypotheses about the interaction between behavior and metabolism. By contrast, the applied researcher is likely to study eating because there are children who eat too little and adults who eat too much, and he will study eating in exactly those individuals”.

Applied therefore means that ABA focuses on the study and teaching of socially significant behaviors, useful to increase the well-being and autonomy of that specific person.

When drawing up a behavioral plan, you must always ask yourself what are the priority objectives to be identified as the target of the intervention and focus on them, before thinking about interventions for objectives of lesser importance at that time.

Teaching a child to categorize different types of clothes according to the seasons, for example, might be appropriate at a certain time for a child with certain characteristics, but it might not be appropriate for another child who, for example, lacked the ability to ask for what he needs or to name simple objects.

Second dimension: Behavioral

According to the authors, “since the behavior of an individual is composed of physical events, its scientific study requires their precise measurement”.

The focus of the study and intervention in ABA is the directly observable and, therefore, measurable behavior.

Behaviors are measured using parameters such as duration, frequency, latency, intensity.

To measure and, later, intervene on a certain behavior, it will be necessary to define it precisely in an operational way.

No generic definitions, inferences or “mentalisms” are used.

For example, a correct operational definition will be: “I want to measure the monthly frequency of pinchings defined as grips inflicted on the body of others with fingers”. And not: “I want to measure the boy’s aggressive behavior”.

“I want to measure the number of requests (mands) that the child emits in 4 hours with the delivery of a card”. And not: “I want to measure the child’s learning”.

“Behaviorism and pragmatism often seem to go hand in hand. Applied research is eminently pragmatic; it asks how it is possible to get an individual to do something effectively”.

Third dimension: Analytic

According to the authors, “the analysis of a behavior requires a believable demonstration of the events that can be responsible for the occurrence or non-occurrence of that behavior”.

ABA identifies clear functional relationships between the manipulated variable (independent variable) and the behavior under study (dependent variable).

The researcher manipulates environmental stimuli in order to identify any causal relationships between the behavior and the environment.

To do this, the behavior analyst uses data collection and precise experimental designs.

Baer, Wolf and Risley cited two of the most important experimental designs used in ABA: reversal design and multiple baseline design.

- In the reversal design, “a behavior is measured, and the measure is examined over time until its stability is clear. Then, the experimental variable is applied. The behavior continues to be measured, to see if the variable will produce a behavioral change. If it does, the experimental variable is discontinued or altered, to see if the behavioral change just brought about depends on it. If so, the behavioral change should be lost or diminished (thus the term “reversal”). The experimental variable then is applied again, to see if the behavioral change can be recovered”.

- “In the multiple-baseline technique, a number of responses are identified and measured over time to provide baselines against which changes can be evaluated. With these baselines established, the experimenter then applies an experimental variable to one of the behaviors, produces a change in it, and perhaps notes little or no change in the other baselines. If so, he applies the experimental variable to one of the other, as yet unchanged, responses. If it changes at that point, evidence is accruing that the experimental variable is indeed effective, and that the prior change was not simply a matter of coincidence. The variable then may be applied to still another response, and so on”.

Fourth dimension: Technological

In ABA, all the procedures are described in an analytical and precise way, in order to be replicated by anyone who needs to apply them.

ABA protocols must describe all steps of the procedures in a detailed and complete way.

According to the authors, “technological means simply that the techniques making up a particular behavioral application are completely identified and described.

In this sense, “play therapy” is not a technological description, nor is “social reinforcement“.

For purposes of application, all the salient ingredients of play therapy must be described as a set of contingencies between child response, therapist response, and play materials.

Similarly, all the ingredients of social reinforcement must be specified (stimuli, contingency, and schedule) to qualify as a technological procedure.

The best rule of thumb for evaluating a procedure description as technological is probably to ask whether a typically trained reader could replicate that procedure well enough to produce the same results, given only a reading of the description”.

Fifth dimension: Conceptual Systems

ABA procedures derive directly from the principles of behavioral science and are procedures of proven scientific evidence and efficacy.

All non-evidence-based interventions, that is to say interventions for which scientific research has not produced evidence of efficacy, are excluded.

When preparing an ABA protocol, you must always ask yourself whether all the steps described are consistent with the principles and laws of behavior. We must never leave the field of scientific evidence.

ABA protocols must not only be technological (described in a precise and analytical way), but must also contain references to the principles from which the procedures derive.

For example, to quote the words of the authors, “to describe the exact sequence of color changes whereby a child is moved from a color discrimination to a form discrimination is good; to refer also to “fading” and “errorless discrimination” is better.

In both cases, the total description is adequate for successful replication by the reader; and it also shows the reader how similar procedures may be derived from basic principles.

This can have the effect of making a body of technology into a discipline rather than a collection of tricks.

Collections of tricks historically have been difficult to expand systematically, and when they were extensive, difficult to learn and teach”.

Sixth dimension: Effective

Interventions based on ABA must be effective.

The principles of behavior are not many and are universal (valid for all human beings); on the other hand, the specific procedures in which they are declined can be infinite, depending on the individual characteristics of the person to whom they are addressed.

The procedures must be tailored to the individual. It is data that guide our intervention. The scientific method is applied.

Do data show us that our intervention is effective?

If data do not go in the direction of effectiveness, this means that changes must be made.

Data allow us to evaluate the effectiveness of an ongoing intervention and, possibly, to replace it or to change some variables.

If the intervention is effective, how much is it effective?

How fast is the change taking place? We must always ask ourselves these questions, always bearing in mind that the changes to be produced must be socially significant and must achieve important results for the person.

To quote the authors: “non-applied research often may be extremely valuable when it produces small but reliable effects, in that these effects testify to the operation of some variable which in itself has great theoretical importance.

In application, the theoretical importance of a variable is usually not at issue. Its practical importance, specifically its power in altering behavior enough to be socially important, is the essential criterion”.

The objective is therefore the real improvement of the quality of life.

“A pertinent question can be, how much did that behavior need to be changed?”

Seventh dimension: Generality

An ABA-based intervention will be all the more effective the more the person will be able to generalize the acquired skills when in different environments, with different people and in relation to different behaviors.

Generalization is not something that always happens automatically, but in many cases it has to be planned with specific interventions.

For example, if I teach a child to name (tact) an apple when he sees a red apple, it is not certain that he will automatically generalize his learning to yellow apples, or to pictures of apples.

In some cases, I will have to plan the learning for this to happen.

Similarly, if a boy reduces his spitting behavior when he goes for a walk with his educators, he will not necessarily automatically reduce it when he is in the playground. In some cases, generalization happens automatically, in other cases generalization interventions have to be planned.

To quote the authors: “a behavioral change may be said to have generality if it proves durable over time, if it appears in a wide variety of possible environments, or if it spreads to a wide variety of related behaviors. In general, generalization should be programmed, rather than expected or lamented”.

For the purposes of generalization, it is important to conduct an ABA intervention in the natural environment, that is to say in the environments that the person frequents in everyday life.

It is therefore not advisable to run the ABA programs always and only in the educational center, but interventions that involve all contexts, home, school, sports center, park and so on, should be planned.

“Education is what survives when what has been learned is forgotten” (Skinner).

Sources: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1310980/